προαιρεῖσθαί τε δεῖ ἀδύνατα εἰκότα μᾶλλον ἢ δυνατὰ ἀπίθανα

What is convincing though impossible should always be preferred to what is possible and unconvincing. Aristotle, Poetics, 1460a

A final thought -- more like a trial balloon -- on Paradiso 32, in an effort to put this enigmatic canto in some "light" that takes note of its critical place in the Commedia.

The absence of voice, song, and light (luce appears not at all, and lume appears once in the canto - each word appears five times in canto 33) sets it apart from what we've been used to in the canticle.

Bernard carefully delineates the divisions that run like cicatrices through the Rose, but no systematic explanation for this order rather than any other is revealed. Historical facts are presented, but not illuminated by reason (logos). Also, the finite detail of these 18 beings stands in stark contrast to many precedent scenes of illimitable constellations of angels and souls.

Women from Eve down through the Old Testament form the wall, bracketed by Mary, linked through the piaga, the opening wound marking the genesis and inscription of human history upon flesh. The stories from the Old Testament involve love, wiles, violence, seduction, willingness to take heroic risks, and merciful, healing care.

Grandgent and others have noted that the "seating" in the Rose has no apparent order. Mary is clearly the solar pinnacle of the Rose; next comes Eve; the series continues, but disobeys categories such as historical or ethnic order. One can say that the persons in this wall (except Mary) are women whose names are found in the Old Testament.

Readers seeking rational closure will pull out their hair asking "why these people and not these people?" Bernard is a subtle and sophisticated interpreter of the Song of Songs and other Old Testament texts. But, when he says . . .

Ne l'ordine che fanno i terzi sedi,

siede Rachel di sotto da costei

con Bëatrice, sì come tu vedi.

Within that order which the third seats make

Is seated Rachel, lower than the other,

With Beatrice, in manner as thou seest. (32: 7-9)

The series of Old Testament figures stubbornly defeats neat ordering schemes, just as the history of the stiff-necked Jews is a broken tale, rich in promise, failure, disaster, and unforeseeable rescues. We are left with an incomplete, seemingly arbitrary, unspeaking, dimly lit congeries of names and events, which we call the word of God.

τούς τε λόγους μὴσυνίστασθαι ἐκ μερῶν ἀλόγων, ἀλλὰ μάλιστα μὲν μηδὲν ἔχειν ἄλογον, εἰ δὲ μή, ἔξωτοῦ μυθεύματος,

so far as possible there should be nothing inexplicable, or, if there is, it should lie outside the story. Poetics 1460a.

Io vidi sopra lei tanta allegrezza

piover, portata ne le menti sante

create a trasvolar per quella altezza,

che quantunque io avea visto davante,

di tanta ammirazion non mi sospese,

né mi mostrò di Dio tanto sembiante;

On her did I behold so great a gladness

Rain down, borne onward in the holy minds

Created through that altitude to fly,

That whatsoever I had seen beforeWith the affetto of this allegrezza, the silence of the canto turns to music. Courtly Gabriel gracefully enacts the anomalous grace of the Annunciation, bringing an unthinkable choice to receive the divine seed, logos spermatikos.

Did not suspend me in such admiration,

Nor show me such similitude of God. (32: 88-93)

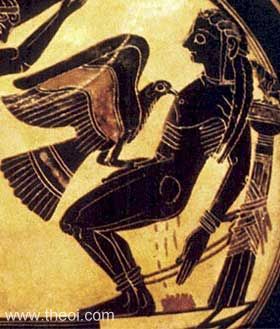

Zeus is not bearing off a bull-beguiled Europa; Apollo is not frustrated by unwilling Daphne; Hades is not dragging the virgin Persephone into the Underworld. The pivotal moment of human history hangs in this suspension, waiting upon the free consent of a young girl.

Nel ventre tuo si raccese l'amore,When in the final canto Bernard echoes Gabriel's greeting, he puts into narrative form the betrothed virgin's's unforced assent to plant that seed in her ventre, grounding the fiore of immortal life in history.

per lo cui caldo ne l'etterna pace

così è germinato questo fiore. (Par. 33:7-9)

What divine power would allow the fall, the damnation and so much suffering to flow from one couple's decision in a garden, then provide his beloved own son as sacrifice so that the species of those who killed him could accede to the possibility of a seat in heaven? You couldn't make this up --- it lies "outside the story."

This is not what sensible people like Aristotle would describe as probable (mimetic) behavior. The twists and turns of the Jewish people, the story of the Virgin and her son and the entire history of Creation achieve intelligibility only if we accept an ebullient suspension, a wounding rift in the logic and conventions of history. It breaks into two covenants, one before, one after, Mary's assent.

So here's my trial balloon: Canto 32 is unadorned and fails to have an ending because it stands in relation to Paradiso 33 as the Old Covenant to the New. The literal features of canto 32 -- the obvious lack of poetry -- stripped of imaginative fire, of light, of sonority -- lend a forbidding aspect to this bewildering tale that arrives at no conclusion.

What other poet would do what Dante does here? At the portal to the godhead, Canto 32 remembers the human experience of being in the dark. When, like Ugolino, we are imprisoned, groping in darkness, discovering to our horror that we are stumbling on the bodies of our children whose death is our paternal legacy, the canto leaves one thing left to do: To act, to pray with all one's affetto.

E cominciò questa santa orazione:Canto 32 is to Paradiso 33 as the Old Testament is to the New, or as the dim human realm is to exorbitant splendor and sweetness of the Rose. One turns, as the Creator did, to the Virgin and asks for help.

Note there are no male heroes named in 32. No Joseph, no Abraham. Moses and David get a sideways glance. The wings of this poet are powered by the oriafiamme. Cherchez la femme.