I saw Heidegger then as one of many thinkers who believe humanity took a wrong turn of thought or action that distorted its true nature. Science takes space and time, the framework of all possible reality, and in studying them as formal entities, disenchants them, destroying them forever as home to belief. What if, Heidegger asked, another more primal way of knowing, one that accords with our status as humans—that is, as the only creatures whose being (what am I? why am I here?) is a question—has been hidden by purely rational or instrumental modes of thinking?The larger context of this article by Stephen Metcalf has to do with Martin Heidegger's fascism. This capsule description of the German philosopher's narrative of the present human predicament suggests how Heidegger links to Existentialism - he offers a story of our alienation from some more primal, paradisal condition. This in turn might prompt some thinking about how the "story behind the story" of some 20th Century philosophical concerns relates to the fundamental plot of fall, error, underlying the tradition Milton is taking on in Paradise Lost.

Sunday, May 30, 2010

Heidegger and error

Friday, May 28, 2010

Lines on Milton

Three poets, in three distant ages born,

Greece, Italy, and England, did adorn.

The first in loftiness of thought surpass'd,

The next in majesty, in both the last:

The force of Nature could no farther go;

To make a third she join'd the former two.

Here's an article about Dryden's "crime" of fitting Paradise Lost into rhymed couplets, titling it The State of Innocence and Fall of Man, an Opera, Written in Heroic Verse. If JSTOR's walled garden approach to knowledge frustrates your desire to read the whole piece, let me know.

Wednesday, May 26, 2010

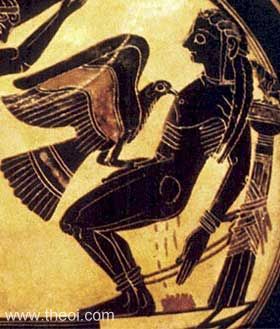

Prometheus

|

| Prometheus bound, Laconian black-figure amphoriskos C6th B.C., Vatican City Museums |

As punishment for these rebellious acts, Zeus ordered the creation of Pandora (the first woman) as a means to deliver misfortune into the house of man, or as a way to cheat mankind of the company of the good spirits. Prometheus meanwhile, was arrested and bound to a stake on Mount Kaukasos where an eagle was set to feed upon his ever-regenerating liver (or, some say, heart). Generations later the great hero Herakles came along and released the old Titan from his torture.

Prometheus was loosely identified in cult and myth with the fire-god Hephaistos and the giant Tityos.

Monday, May 24, 2010

Hyper-Concordance: Another powerful tool

"Fall" occurs 64 times in Paradise Lost. "Wonder" is found 21 times. You can search these and other words, and immediately see their contexts, via this Hyper-Concordance.

Here's the results for "wander":

519: Darkens the Streets, then wander forth the Sons Of BELIAL, flown with

976: being, Those thoughts that wander through Eternity, To perish rather,

1940: Yet not the more Cease I to wander where the Muses haunt Cleer Spring, or

2383: Till final dissolution, wander here, Not in the neighbouring Moon, as

5644: I fall Erroneous, there to wander and forlorne. Half yet remaines unsung,

5966: where Gods might dwell, Or wander with delight, and love to haunt Her

9643: shall I part, and whither wander down Into a lower World, to this obscure

Look up any word and find its use and contexts through this Hyper-Concordance. And not just in Paradise Lost - many of Milton's works are here, as are, in fact, works of Ben Jonson, Samuel Johnson, Jonathan Swift, W.B. Yeats, T.S. Eliot, Sterne, Smollett, Richardson, Emerson, Whitman, and many more. It's part of the Victorian Literary Studies Archive.

Here's the results for "wander":

519: Darkens the Streets, then wander forth the Sons Of BELIAL, flown with

976: being, Those thoughts that wander through Eternity, To perish rather,

1940: Yet not the more Cease I to wander where the Muses haunt Cleer Spring, or

2383: Till final dissolution, wander here, Not in the neighbouring Moon, as

5644: I fall Erroneous, there to wander and forlorne. Half yet remaines unsung,

5966: where Gods might dwell, Or wander with delight, and love to haunt Her

9643: shall I part, and whither wander down Into a lower World, to this obscure

Look up any word and find its use and contexts through this Hyper-Concordance. And not just in Paradise Lost - many of Milton's works are here, as are, in fact, works of Ben Jonson, Samuel Johnson, Jonathan Swift, W.B. Yeats, T.S. Eliot, Sterne, Smollett, Richardson, Emerson, Whitman, and many more. It's part of the Victorian Literary Studies Archive.

Mario Livio on the enigma of knowledge

Excerpt from a longer, fascinating interview here:

Ms. Tippett: … and you end up with all these puzzles or mysteries that feel to me that they're verging on the philosophical and the theological as well, right, by implication. So you can say that our minds give rise to mathematics but then mathematics are found to explain the physical world.

Mr. Livio: That's right.

Ms. Tippett: Which is a very mysterious thing to think about.

Mr. Livio: Yeah. You're absolutely right. And, you know, my colleague Roger Penrose, I don't know if you've ever interviewed him …

Ms. Tippett: I haven't, but I know his work. Yeah.

Mr. Livio: Yeah. So he's a very famous mathematical physicist. So he once said that there are at least three worlds and three mysteries.

Ms. Tippett: Mm-hmm.

Mr. Livio: So the three worlds are, one is the physical world. You know, this is the world where we exist. There are chairs, tables, there are stars, there are galaxies, and so on. Then there is a second world, which is the world of our consciousness, if you like. You know, a mental world, a world where this is where we love, where we hate, you know, and so on. All our thoughts are there and so on. And then there is the third world, which is this world of mathematical forms. This is the world where all of mathematics is there. You know, the theorem of Pythagoras and so on and so forth, all the imaginary numbers and all that. So these are the three worlds. And now come these three mysteries. One mystery is that somehow, out of the physical world, our world of consciousness has emerged. That's one mystery.

Ms. Tippett: Right. Right.

Mr. Livio: A second mystery is that somehow our world of consciousness or mental world gained access to this world of mathematical form. You know, that we were able to invent and discover all these mathematics. And third, and maybe most amazing mystery, is that we find that this world of mathematics provides the explanations for the physical world.

Ms. Tippett: Right. Right. So it's that circle again.

Mr. Livio: Right. So there are these three worlds and three mysteries which, you know, of course at the end of the day they are all part of one universe, right? But it's an interesting way of posing the question.

Saturday, May 22, 2010

Eve, Pandora and Prometheus

But wherfore all night long shine these, for whom

This glorious sight, when sleep hath shut all eyes?

Eve's question leads to a passage that moves from astronomical conjecture to Greek myth, ending with:

More lovely then Pandora, whom the Gods

Endowd with all thir gifts, and O too like [ 715 ]

In sad event, when to the unwiser Son

Of Japhet brought by Hermes, she ensnar'd

Mankind with her faire looks, to be aveng'd

On him who had stole Joves authentic fire.

The linking of light, fire, woman, curiosity, forbidden knowledge and disaster has roots both in Eden and in Greece. Here's the gift of Pandora from Hesiod's Theogony:

This glorious sight, when sleep hath shut all eyes?

Eve's question leads to a passage that moves from astronomical conjecture to Greek myth, ending with:

More lovely then Pandora, whom the Gods

Endowd with all thir gifts, and O too like [ 715 ]

In sad event, when to the unwiser Son

Of Japhet brought by Hermes, she ensnar'd

Mankind with her faire looks, to be aveng'd

On him who had stole Joves authentic fire.

The linking of light, fire, woman, curiosity, forbidden knowledge and disaster has roots both in Eden and in Greece. Here's the gift of Pandora from Hesiod's Theogony:

But the noble son of Iapetus outwitted him and stole the far-seen gleam of unwearying fire in a hollow fennel stalk. And Zeus who thunders on high was stung in spirit, and his dear heart was angered when he saw amongst men the far-seen ray of fire. Forthwith he made an evil thing for men as the price of fire; for the very famous Limping God formed of earth the likeness of a shy maiden as the son of Cronos willed. And the goddess bright-eyed Athene girded and clothed her with silvery raiment, and down from her head she spread with her hands a broidered veil, a wonder to see; and she, Pallas Athene, put about her head lovely garlands, flowers of new-grown herbs. Also she put upon her head a crown of gold which the very famous Limping God made himself and worked with his own hands as a favour to Zeus his father. On it was much curious work, wonderful to see; for of the many creatures which the land and sea rear up, he put most upon it, wonderful things, like living beings with voices: and great beauty shone out from it.

[585] But when he had made the beautiful evil to be the price for the blessing, he brought her out, delighting in the finery which the bright-eyed daughter of a mighty father had given her, to the place where the other gods and men were. And wonder took hold of the deathless gods and mortal men when they saw that which was sheer guile, not to be withstood by men.

[590] For from her is the race of women and female kind: of her is the deadly race and tribe of women who live amongst mortal men to their great trouble, no helpmeets in hateful poverty, but only in wealth. And as in thatched hives bees feed the drones whose nature is to do mischief -- by day and throughout the day until the sun goes down the bees are busy and lay the white combs, while the drones stay at home in the covered skeps and reap the toil of others into their own bellies – even so Zeus who thunders on high made women to be an evil to mortal men, with a nature to do evil. And he gave them a second evil to be the price for the good they had: whoever avoids marriage and the sorrows that women cause, and will not wed, reaches deadly old age without anyone to tend his years, and though he at least has no lack of livelihood while he lives, yet, when he is dead, his kinsfolk divide his possessions amongst them. And as for the man who chooses the lot of marriage and takes a good wife suited to his mind, evil continually contends with good; for whoever happens to have mischievous children, lives always with unceasing grief in his spirit and heart within him; and this evil cannot be healed.

[613] So it is not possible to deceive or go beyond the will of Zeus; for not even the son of Iapetus, kindly Prometheus, escaped his heavy anger, but of necessity strong bands confined him, although he knew many a wile.

Images of Pandora from Theoi.

Wednesday, May 19, 2010

The generous universe

now glow'd the Firmament

With living Saphirs: Hesperus that led [ 605 ]

The starrie Host, rode brightest, till the Moon

Rising in clouded Majestie, at length

Apparent Queen unvaild her peerless light,

And o're the dark her Silver Mantle threw.

This lovely passage in Book IV serves as the transition from day to evening to night, with the glow of the "living Saphirs" granting pride of place to Hesperus, the evening star -- we might recall the evocation of the same star, but charged with Christian significance, in Lycidas:

So sinks the day-star in the Ocean bed,

And yet anon repairs his drooping head,

And tricks his beams, and with new-spangled Ore, [ 170 ]

Flames in the forehead of the morning sky:

In this pre-Christian, unfallen moment, Hesperus cedes her lead to the mutable moon which, even as it rises, undergoes bewitching tranformation, from veiled Majestie to naked, dominant queen of the night, throwing her silver mantle over the dark. So there are at least four levels of light in this one brief passage, with the unveiling of the moon occurring in unison with the mantling of the earth. (Prof. Rogers noted how in Lycidas there's a tantalizing ambiguity near the end, where the grammar allows for either the sun, or the singer/shepherd, to have "twitch'd his Mantle blew.")

As several of us noted, there is undeniably an element of Fairie, of Midsummer Night and Ariel, in this portion of the poem.

The sense of a world alive with spirit-presences carries forward with Adam's next response to Eve's question about the stars:

But wherfore all night long shine these, for whom

This glorious sight, when sleep hath shut all eyes?

Adam says:

Millions of spiritual Creatures walk the Earth

Unseen, both when we wake, and when we sleep:

And

how often from the steep [ 680 ]

Of echoing Hill or Thicket have we heard

Celestial voices to the midnight air,

Sole, or responsive each to others note

Singing thir great Creator

They hear a lot of night music - as Pythagoras once suggested we once could hear the Music of the Spheres, until it faded.

As discussed, Adam and Eve are in some ways childlike - they know nothing of death, law, or taxes. Property does not loom large; all creatures possess the earth, air, and seas. It is in that first wonderment, the musings of the child, that Milton chooses to situate a sense of utter plenitude - a universe that is seething, infinite, not simply in size, but in populations - teeming with birds, insects, stars.

This apprehension of Being as the opposite of Void - of an overflowing generousness of creative power -- is not uncommon in early myth, and seems to be almost a working hypothesis of any poet you name, be it Hesiod, Shakespeare, or Whitman. It's also, if this is not too Borgesian to suggest, the preferred hypothesis of the Standard Model of particle physics and of string theory. That is to say, our advanced scientific probings of the universe find wheels within wheels, quarks within atoms, strings within all things.

With living Saphirs: Hesperus that led [ 605 ]

The starrie Host, rode brightest, till the Moon

Rising in clouded Majestie, at length

Apparent Queen unvaild her peerless light,

And o're the dark her Silver Mantle threw.

This lovely passage in Book IV serves as the transition from day to evening to night, with the glow of the "living Saphirs" granting pride of place to Hesperus, the evening star -- we might recall the evocation of the same star, but charged with Christian significance, in Lycidas:

So sinks the day-star in the Ocean bed,

And yet anon repairs his drooping head,

And tricks his beams, and with new-spangled Ore, [ 170 ]

Flames in the forehead of the morning sky:

In this pre-Christian, unfallen moment, Hesperus cedes her lead to the mutable moon which, even as it rises, undergoes bewitching tranformation, from veiled Majestie to naked, dominant queen of the night, throwing her silver mantle over the dark. So there are at least four levels of light in this one brief passage, with the unveiling of the moon occurring in unison with the mantling of the earth. (Prof. Rogers noted how in Lycidas there's a tantalizing ambiguity near the end, where the grammar allows for either the sun, or the singer/shepherd, to have "twitch'd his Mantle blew.")

As several of us noted, there is undeniably an element of Fairie, of Midsummer Night and Ariel, in this portion of the poem.

The sense of a world alive with spirit-presences carries forward with Adam's next response to Eve's question about the stars:

But wherfore all night long shine these, for whom

This glorious sight, when sleep hath shut all eyes?

Adam says:

Millions of spiritual Creatures walk the Earth

Unseen, both when we wake, and when we sleep:

And

how often from the steep [ 680 ]

Of echoing Hill or Thicket have we heard

Celestial voices to the midnight air,

Sole, or responsive each to others note

Singing thir great Creator

They hear a lot of night music - as Pythagoras once suggested we once could hear the Music of the Spheres, until it faded.

As discussed, Adam and Eve are in some ways childlike - they know nothing of death, law, or taxes. Property does not loom large; all creatures possess the earth, air, and seas. It is in that first wonderment, the musings of the child, that Milton chooses to situate a sense of utter plenitude - a universe that is seething, infinite, not simply in size, but in populations - teeming with birds, insects, stars.

This apprehension of Being as the opposite of Void - of an overflowing generousness of creative power -- is not uncommon in early myth, and seems to be almost a working hypothesis of any poet you name, be it Hesiod, Shakespeare, or Whitman. It's also, if this is not too Borgesian to suggest, the preferred hypothesis of the Standard Model of particle physics and of string theory. That is to say, our advanced scientific probings of the universe find wheels within wheels, quarks within atoms, strings within all things.

Tuesday, May 18, 2010

How to memorize a poem

From the Hartford Courant:

It took John Basinger eight years to memorize John Milton's 17th-century epic poem "Paradise Lost." At about 60,000 words, it's roughly the equivalent of a 350-page novel. It takes Basinger three, eight-hour days to recite the work in its entirety.

Monday, May 17, 2010

Laughable otherworldliness

Apropos the deep association of silliness and philosophy, Mussy points us to this essay by Simon Critchley. A snippet:

"What is a philosopher, then? The answer is clear: a laughing stock, an absent-minded buffoon, the butt of countless jokes from Aristophanes’ “The Clouds” to Mel Brooks’s “History of the World, part one.” Whenever the philosopher is compelled to talk about the things at his feet, he gives not only the Thracian girl but the rest of the crowd a belly laugh. The philosopher’s clumsiness in worldly affairs makes him appear stupid or, “gives the impression of plain silliness.” We are left with a rather Monty Pythonesque definition of the philosopher: the one who is silly."

Wednesday, May 12, 2010

More and less random links

Here's a film about Jorge Luis Borges, "who longed for oblivion, and who believed happiness existed somewhere between the pages of a book."

A somewhat superficial NPR treatment of hair covering and its roots in various religions.

From Mussy: Luminarium Anthology English Literature - selections of 17th Century authors for the Summer.

A somewhat superficial NPR treatment of hair covering and its roots in various religions.

From Mussy: Luminarium Anthology English Literature - selections of 17th Century authors for the Summer.

Thursday, May 06, 2010

Paul pilpul

As we found yesterday with regard to I Corinthians 11, it's less easy to "follow" Paul, to read him, than it first might seem.

Two footnotes: Paul's word for "follow" is the greek mimetai, the root of mimesis - to imitate, copy - the same word the Greeks used to speak of art, as when Aristotle says a plot is the "imitation of an action."

Paul's word for "glory" is doxa - this word seems to have undergone a curious transformation when the Bible was translated into Greek (the Septuagint, in Alexandria in the 3rd and 2nd centuries BC). For Aristotle and Plato, the word carried the sense of "opinion" in contrast with "knowledge," scientific certitude. The translators of the Old Testament used doxa to render the Hebrew kavod, "glory," according to this note. New Testament writers seem to have employed that acceptation.

Here's a modern English translation of Paul's passage, from the World English Bible.

The passage in question, I Corinthians 11 1-13, is sufficiently intractable as to have permitted radically incompatible readings, according to this note in Wikipedia:

Bushnell view

A minority translate the passage as commanding women to uncover their heads. This idea was pioneered by John Lightfoot and expanded by Katharine Bushnell. In their view, Paul commanded women to uncover because they were made in the image of God, Eve was created for Adam's incapacity to exist alone, all men are born from women, because of her angels, nature does not teach otherwise, and the churches have no such custom. The passage is not actually a repression of women but a herald for equality. However, no printed Bibles have accepted this translation.

Pilpul indeed!

Tuesday, May 04, 2010

Following Paul

After situating mankind vis a vis the other living creatures, Paradise Lost turns to the relation of the sexes in IV.300 ff:

Not equal, as thir sex not equal seemd;

For contemplation hee and valour formd,

For softness shee and sweet attractive Grace,

Hee for God only, shee for God in him

:His fair large Front and Eye sublime declar'd [ 300 ]

Absolute rule; and Hyacinthin Locks

Round from his parted forelock manly hung

Clustring, but not beneath his shoulders broad:

Shee as a vail down to the slender waste

Her unadorned golden tresses wore [ 305 ]

Disheveld, but in wanton ringlets wav'd

As the Vine curles her tendrils, which impli'd

Subjection, but requir'd with gentle sway,

And by her yielded, by him best receivd,

Yielded with coy submission, modest pride, [ 310 ]

And sweet reluctant amorous delay.

Nor those mysterious parts were then conceald,

Then was not guiltie shame, dishonest shame

Of natures works, honor dishonorable,

Sin-bred, how have ye troubl'd all mankind [ 315 ]

With shews instead, meer shews of seeming pure,

And banisht from mans life his happiest life,

Simplicitie and spotless innocence.

So passd they naked on, nor shund the sight

Of God or Angel, for they thought no ill: [ 320 ]

So hand in hand they passd, the lovliest pair

That ever since in loves imbraces met,

Adam the goodliest man of men since borne

His Sons, the fairest of her Daughters Eve.

As noted, Milton is largely following Paul, who begins the chapter from Paul's I Corinthians Ch. 11 by talking about following. Here it is in the KJV:

1 Be ye followers of me, even as I also am of Christ.

2 Now I praise you, brethren, that ye remember me in all things, and keep the ordinances, as I delivered them to you.

3 But I would have you know, that the head of every man is Christ; and the head of the woman is the man; and the head of Christ is God.

4Every man praying or prophesying, having his head covered, dishonoureth his head.

5But every woman that prayeth or prophesieth with her head uncovered dishonoureth her head: for that is even all one as if she were shaven.

6For if the woman be not covered, let her also be shorn: but if it be a shame for a woman to be shorn or shaven, let her be covered.

7For a man indeed ought not to cover his head, forasmuch as he is the image and glory of God: but the woman is the glory of the man.

8For the man is not of the woman: but the woman of the man.

9Neither was the man created for the woman; but the woman for the man.

10For this cause ought the woman to have power on her head because of the angels.

11Nevertheless neither is the man without the woman, neither the woman without the man, in the Lord.

12For as the woman is of the man, even so is the man also by the woman; but all things of God.

13Judge in yourselves: is it comely that a woman pray unto God uncovered?

14Doth not even nature itself teach you, that, if a man have long hair, it is a shame unto him?

15But if a woman have long hair, it is a glory to her: for her hair is given her for a covering.

Monday, May 03, 2010

Pico's Creation of Man

Count Giovanni Pico della Mirandola was all of 23 in 1486 when he published his 900 Theses to the world, proposing to defend them against all comers, and even to pay travelling expenses for scholars coming from afar. More about Pico here.

His Oration on the Dignity of Man was composed to accompany and introduce the theses. Nearly at the beginning Pico offers his own version of the creation story, which immediately assumed a key place in the history of Renaissance thought and of Humanism. The entire oration, which he never gave (his initiative was suppressed by the Church), is worth reading; here's his story of the creation of Man:

His Oration on the Dignity of Man was composed to accompany and introduce the theses. Nearly at the beginning Pico offers his own version of the creation story, which immediately assumed a key place in the history of Renaissance thought and of Humanism. The entire oration, which he never gave (his initiative was suppressed by the Church), is worth reading; here's his story of the creation of Man:

God the Father, the Mightiest Architect, had already raised, according to the precepts of His hidden wisdom, this world we see, the cosmic dwelling of divinity, a temple most august. He had already adorned the supercelestial region with Intelligences, infused the heavenly globes with the life of immortal souls and set the fermenting dung-heap of the inferior world teeming with every form of animal life. But when this work was done, the Divine Artificer still longed for some creature which might comprehend the meaning of so vast an achievement, which might be moved with love at its beauty and smitten with awe at its grandeur. When, consequently, all else had been completed (as both Moses and Timaeus testify), in the very last place, He bethought Himself of bringing forth man. Truth was, however, that there remained no archetype according to which He might fashion a new offspring, nor in His treasure-houses the wherewithal to endow a new son with a fitting inheritance, nor any place, among the seats of the universe, where this new creature might dispose himself to contemplate the world. All space was already filled; all things had been distributed in the highest, the middle and the lowest orders. Still, it was not in the nature of the power of the Father to fail in this last creative élan; nor was it in the nature of that supreme Wisdom to hesitate through lack of counsel in so crucial a matter; nor, finally, in the nature of His beneficent love to compel the creature destined to praise the divine generosity in all other things to find it wanting in himself.

At last, the Supreme Maker decreed that this creature, to whom He could give nothing wholly his own, should have a share in the particular endowment of every other creature. Taking man, therefore, this creature of indeterminate image, He set him in the middle of the world and thus spoke to him:

``We have given you, O Adam, no visage proper to yourself, nor endowment properly your own, in order that whatever place, whatever form, whatever gifts you may, with premeditation, select, these same you may have and possess through your own judgement and decision. The nature of all other creatures is defined and restricted within laws which We have laid down; you, by contrast, impeded by no such restrictions, may, by your own free will, to whose custody We have assigned you, trace for yourself the lineaments of your own nature. I have placed you at the very center of the world, so that from that vantage point you may with greater ease glance round about you on all that the world contains. We have made you a creature neither of heaven nor of earth, neither mortal nor immortal, in order that you may, as the free and proud shaper of your own being, fashion yourself in the form you may prefer. It will be in your power to descend to the lower, brutish forms of life; you will be able, through your own decision, to rise again to the superior orders whose life is divine.''

... a pure contemplator, unmindful of the body, wholly withdrawn into the inner chambers of the mind, here indeed is neither a creature of earth nor a heavenly creature, but some higher divinity, clothed in human flesh....

Sunday, May 02, 2010

Enter: Two

PL IV 288 ff:

Our first view of Adam and Eve is a crucial moment in the poem -- this is where Milton in a sense has to declare himself -- present and situate humanity in its moment of origin, carrying, if you will, the pristine image of the intention of the maker.

Presumably Hobbes would have given us a different image.

Before we look at other images of man to compare, it's worth pondering some of the words Milton chooses here:

Two of far nobler shape erect and tall,

Godlike erect, with native Honour clad

In naked Majestie seemd Lords of all, [ 290 ]

And worthie seemd, for in thir looks Divine

The image of thir glorious Maker shon,

Truth, wisdome, Sanctitude severe and pure,

Severe but in true filial freedom plac't;

Whence true autority in men; though both [ 295 ]

Not equal, as thir sex not equal seemd;

For contemplation hee and valour formd,

For softness shee and sweet attractive Grace,

Hee for God only, shee for God in him:

Our first view of Adam and Eve is a crucial moment in the poem -- this is where Milton in a sense has to declare himself -- present and situate humanity in its moment of origin, carrying, if you will, the pristine image of the intention of the maker.

Presumably Hobbes would have given us a different image.

Before we look at other images of man to compare, it's worth pondering some of the words Milton chooses here:

Lords, image, severe, filial freedom, native honour, naked majestie, looks, truth, wisdome, sanctitude, true autority, contemplation, valour, softness, attractive, Grace. Let's not forget some other key parts of speech: erect, tall, shon, severe, pure, seemed, not equal, for and in.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)