Wednesday, October 31, 2007

Canto 29: Augustine on Language and Time

Augustine, Confessions -

11.28.37

But how is that future diminished or consumed, which as yet is not? or how that past increased, which is now no longer, save that in the mind which enacteth this, there be three things done? For it expects, it considers, it remembers; that so that which it expecteth, through that which it considereth, passeth into that which it remembereth. Who therefore denieth, that things to come are not as yet? and yet, there is in the mind an expectation of things to come. And who denies past things to be now no longer? and yet is there still in the mind a memory of things past. And who denieth the present time hath no space, because it passeth away in a moment? and yet our consideration continueth, through which that which shall be present proceedeth to become absent. It is not then future time, that is long, for as yet it is not: but a long future, is "a long expectation of the future," nor is it time past, which now is not, that is long; but a long past, is "a long memory of the past."

11.28.38

I am about to repeat a Psalm that I know. Before I begin, my expectation is extended over the whole; but when I have begun, how much soever of it I shall separate off into the past, is extended along my memory; thus the life of this action of mine is divided between my memory as to what I have repeated, and expectation as to what I am about to repeat; but "consideration" is present with me, that through it what was future, may be conveyed over, so as to become past. Which the more it is done again and again, so much the more the expectation being shortened, is the memory enlarged: till the whole expectation be at length exhausted, when that whole action being ended, shall have passed into memory. And this which takes place in the whole Psalm, the same takes place in each several portion of it, and each several syllable; the same holds in that longer action, whereof this Psalm may be part; the same holds in the whole life of man, whereof all the actions of man are parts; the same holds through the whole age of the sons of men, whereof all the lives of men are parts.

Original

11.28.37

sed quomodo minuitur aut consumitur futurum, quod nondum est, aut quomodo crescit praeteritum, quod iam non est, nisi quia in animo qui illud agit tria sunt? nam et expectat et attendit et meminit, ut id quod expectat per id quod attendit transeat in id quod meminerit. quis igitur negat futura nondum esse? sed tamen iam est in animo expectatio futurorum. et quis negat praeterita iam non esse? sed tamen adhuc est in animo memoria praeteritorum. et quis negat praesens tempus carere spatio, quia in puncto praeterit? sed tamen perdurat attentio, per quam pergat abesse quod aderit. non igitur longum tempus futurum, quod non est, sed longum futurum longa expectatio futuri est, neque longum praeteritum tempus, quod non est, sed longum praeteritum longa memoria praeteriti est.

11.28.38

dicturus sum canticum quod novi. antequam incipiam, in totum expectatio mea tenditur, cum autem coepero, quantum ex illa in praeteritum decerpsero, tenditur et memoria mea, atque distenditur vita huius actionis meae in memoriam propter quod dixi et in expectationem propter quod dicturus sum. praesens tamen adest attentio mea, per quam traicitur quod erat futurum ut fiat praeteritum. quod quanto magis agitur et agitur, tanto breviata expectatione prolongatur memoria, donec tota expectatio consumatur, cum tota illa actio finita transierit in memoriam. et quod in toto cantico, hoc in singulis particulis eius fit atque in singulis syllabis eius, hoc in actione longiore, cuius forte particula est illud canticum, hoc in tota vita hominis, cuius partes sunt omnes actiones hominis, hoc in toto saeculo filiorum hominum, cuius partes sunt omnes vitae hominum.

11.28.37

But how is that future diminished or consumed, which as yet is not? or how that past increased, which is now no longer, save that in the mind which enacteth this, there be three things done? For it expects, it considers, it remembers; that so that which it expecteth, through that which it considereth, passeth into that which it remembereth. Who therefore denieth, that things to come are not as yet? and yet, there is in the mind an expectation of things to come. And who denies past things to be now no longer? and yet is there still in the mind a memory of things past. And who denieth the present time hath no space, because it passeth away in a moment? and yet our consideration continueth, through which that which shall be present proceedeth to become absent. It is not then future time, that is long, for as yet it is not: but a long future, is "a long expectation of the future," nor is it time past, which now is not, that is long; but a long past, is "a long memory of the past."

11.28.38

I am about to repeat a Psalm that I know. Before I begin, my expectation is extended over the whole; but when I have begun, how much soever of it I shall separate off into the past, is extended along my memory; thus the life of this action of mine is divided between my memory as to what I have repeated, and expectation as to what I am about to repeat; but "consideration" is present with me, that through it what was future, may be conveyed over, so as to become past. Which the more it is done again and again, so much the more the expectation being shortened, is the memory enlarged: till the whole expectation be at length exhausted, when that whole action being ended, shall have passed into memory. And this which takes place in the whole Psalm, the same takes place in each several portion of it, and each several syllable; the same holds in that longer action, whereof this Psalm may be part; the same holds in the whole life of man, whereof all the actions of man are parts; the same holds through the whole age of the sons of men, whereof all the lives of men are parts.

Original

11.28.37

sed quomodo minuitur aut consumitur futurum, quod nondum est, aut quomodo crescit praeteritum, quod iam non est, nisi quia in animo qui illud agit tria sunt? nam et expectat et attendit et meminit, ut id quod expectat per id quod attendit transeat in id quod meminerit. quis igitur negat futura nondum esse? sed tamen iam est in animo expectatio futurorum. et quis negat praeterita iam non esse? sed tamen adhuc est in animo memoria praeteritorum. et quis negat praesens tempus carere spatio, quia in puncto praeterit? sed tamen perdurat attentio, per quam pergat abesse quod aderit. non igitur longum tempus futurum, quod non est, sed longum futurum longa expectatio futuri est, neque longum praeteritum tempus, quod non est, sed longum praeteritum longa memoria praeteriti est.

11.28.38

dicturus sum canticum quod novi. antequam incipiam, in totum expectatio mea tenditur, cum autem coepero, quantum ex illa in praeteritum decerpsero, tenditur et memoria mea, atque distenditur vita huius actionis meae in memoriam propter quod dixi et in expectationem propter quod dicturus sum. praesens tamen adest attentio mea, per quam traicitur quod erat futurum ut fiat praeteritum. quod quanto magis agitur et agitur, tanto breviata expectatione prolongatur memoria, donec tota expectatio consumatur, cum tota illa actio finita transierit in memoriam. et quod in toto cantico, hoc in singulis particulis eius fit atque in singulis syllabis eius, hoc in actione longiore, cuius forte particula est illud canticum, hoc in tota vita hominis, cuius partes sunt omnes actiones hominis, hoc in toto saeculo filiorum hominum, cuius partes sunt omnes vitae hominum.

As early as the third millennium B.C., Mesopotamian scribes began to catalogue the clay tablets in their collections. For ease of reference, they appended content descriptions to the edges of tablets, and they adopted systematic shelving for quick identification of related texts. The greatest and most famous of the ancient collections, the Library of Alexandria, had, in its ambitions and its methods, a good deal in common with Google’s book projects. It was founded around 300 B.C. by Ptolemy I, who had inherited Alexandria, a brand-new city, from Alexander the Great. A historian with a taste for poetry, Ptolemy decided to amass a comprehensive collection of Greek works. Like Google, the library developed an efficient procedure for capturing and reproducing texts. When ships docked in Alexandria, any scrolls found on them were confiscated and taken to the library. The staff made copies for the owners and stored the originals in heaps, until they could be catalogued. At the collection’s height, it contained more than half a million scrolls, a welter of information that forced librarians to develop new organizational methods. For the first time, works were shelved alphabetically. -- Anthony Grafton, "Future Reading," New Yorker.

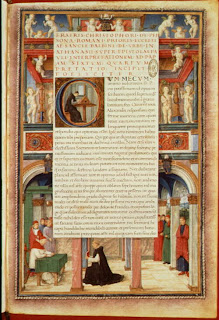

In a separate piece entitled Adventures in Wonderland, Grafton also points to some notable online resources for readers, including Rome Reborn: The Vatican Library & Renaissance Culture.

Wednesday, October 24, 2007

Lash upon Dawkins

For possible future reference, here's a link to a theologian's review of an atheistic scientist's book about God.

The scientist is Richard Dawkins, the book is The God Delusion, and the reviewer is Nicholas Lash.

The possible relevance has to do with the history of the relation of science and religion, since it's come up a few times in our discussions.

The scientist is Richard Dawkins, the book is The God Delusion, and the reviewer is Nicholas Lash.

The possible relevance has to do with the history of the relation of science and religion, since it's come up a few times in our discussions.

Tuesday, October 23, 2007

Terrestrial Paradise

Some images of the Terrestrial Paradise by Flaxman, Blake, Dore and Botticelli are here.

Some commentary is here.

All comes from the University of Texas at Austin's visually impressive site about the Commedia.

Canto 30: The last of Virgil

Alone he wandered, lost Eurydice

Lamenting, and the gifts of Dis ungiven.

Scorned by which tribute the Ciconian dames,

Amid their awful Bacchanalian rites

And midnight revellings, tore him limb from limb,

And strewed his fragments over the wide fields.

Then too, even then, what time the Hebrus stream,

Oeagrian Hebrus, down mid-current rolled,

Rent from the marble neck, his drifting head,

The death-chilled tongue found yet a voice to cry

'Eurydice! ah! poor Eurydice!'

With parting breath he called her, and the banks

From the broad stream caught up 'Eurydice!'"

Virgil, Georgics IV

These are the last words of Orpheus. His story is told within another story involving how Aristaeus learned a method of causing the spontaneous generation of bees.

"Seek not to know," the ghost replied with tears,

"The sorrows of thy sons in future years.

This youth (the blissful vision of a day)

Shall just be shown on earth, and snatch'd away.

The gods too high had rais'd the Roman state,

Were but their gifts as permanent as great.

What groans of men shall fill the Martian field!

How fierce a blaze his flaming pile shall yield!

What fun'ral pomp shall floating Tiber see,

When, rising from his bed, he views the sad solemnity!

No youth shall equal hopes of glory give,

No youth afford so great a cause to grieve;

The Trojan honor, and the Roman boast,

Admir'd when living, and ador'd when lost!

Mirror of ancient faith in early youth!

Undaunted worth, inviolable truth!

No foe, unpunish'd, in the fighting field

Shall dare thee, foot to foot, with sword and shield;

Much less in arms oppose thy matchless force,

When thy sharp spurs shall urge thy foaming horse.

Ah! couldst thou break thro' fate's severe decree,

A new Marcellus shall arise in thee!

Full canisters of fragrant lilies bring,

Mix'd with the purple roses of the spring;

Let me with fun'ral flow'rs his body strow;

This gift which parents to their children owe,

This unavailing gift, at least, I may bestow!"

Aeneid, VI.867-86

The last spoken words of Book VI, the descent of Aeneas into the underworld. The speaker is his father, Anchises, foretelling the future of Rome to his son, its founder.

Lamenting, and the gifts of Dis ungiven.

Scorned by which tribute the Ciconian dames,

Amid their awful Bacchanalian rites

And midnight revellings, tore him limb from limb,

And strewed his fragments over the wide fields.

Then too, even then, what time the Hebrus stream,

Oeagrian Hebrus, down mid-current rolled,

Rent from the marble neck, his drifting head,

The death-chilled tongue found yet a voice to cry

'Eurydice! ah! poor Eurydice!'

With parting breath he called her, and the banks

From the broad stream caught up 'Eurydice!'"

Virgil, Georgics IV

These are the last words of Orpheus. His story is told within another story involving how Aristaeus learned a method of causing the spontaneous generation of bees.

===============

"Seek not to know," the ghost replied with tears,

"The sorrows of thy sons in future years.

This youth (the blissful vision of a day)

Shall just be shown on earth, and snatch'd away.

The gods too high had rais'd the Roman state,

Were but their gifts as permanent as great.

What groans of men shall fill the Martian field!

How fierce a blaze his flaming pile shall yield!

What fun'ral pomp shall floating Tiber see,

When, rising from his bed, he views the sad solemnity!

No youth shall equal hopes of glory give,

No youth afford so great a cause to grieve;

The Trojan honor, and the Roman boast,

Admir'd when living, and ador'd when lost!

Mirror of ancient faith in early youth!

Undaunted worth, inviolable truth!

No foe, unpunish'd, in the fighting field

Shall dare thee, foot to foot, with sword and shield;

Much less in arms oppose thy matchless force,

When thy sharp spurs shall urge thy foaming horse.

Ah! couldst thou break thro' fate's severe decree,

A new Marcellus shall arise in thee!

Full canisters of fragrant lilies bring,

Mix'd with the purple roses of the spring;

Let me with fun'ral flow'rs his body strow;

This gift which parents to their children owe,

This unavailing gift, at least, I may bestow!"

Aeneid, VI.867-86

The last spoken words of Book VI, the descent of Aeneas into the underworld. The speaker is his father, Anchises, foretelling the future of Rome to his son, its founder.

Canto 29: Advent of Pageant

The Order of the Triumphal Progression

- The Senate, headed by the magistrates without their lictors.

- Trumpeters

- Carts with the spoils of war to demonstrate the concrete benefits of the victory

- White bulls for sacrifice

- The arms and insignia of the leaders of the conquered enemy

- The enemy leaders themselves, with their relatives and other captives

- The lictors of the imperator, their fasces wreathed with laurel

- The imperator himself, in a chariot drawn by two (later four) horses

- The adult sons and officers of the imperator

- The army without weapons or armour (since the procession would take them inside the pomerium), but clad to togas and wearing a wreath. During the later periods, only a selected company of soldiers would follow the commander in the triumph.

The imperator himself is painted red and wears a corona triumphalis, a tunica palmata and a toga picta. He is accompanied in the chariot by a slave holding a golden wreath above his head. The slave also constantly reminds the commander of his mortality by whispering into his ear. The exact words are not known for certainty, but the suggestions include "Respica te, hominem te memento" ("Look behind you, you are only a man") and "Memento mori" ("Remember (that you are) mortal").

Often the exact order of triumphal progression was augmented by the triumphator by adding exotic animals, musicians and slaves carrying pictures of conquered cities and signs with names of conquered peoples.

Thursday, October 11, 2007

Translation as Alteration

Shaw points us to another excellent piece from the New Yorker, in which James Wood reviews Robert Alter's new translation of the Psalms. A snippet:

Alter’s translation is especially helpful in these cases, because he is determined to remind his readers that they are reading ancient texts with hybrid origins, not Christian prayers with dedicated destinations. The Psalms (like the Book of Job) were relentlessly Christianized by the King James translators. Nefesh, meaning “life breath” and, by extension, “life,” was translated by Jerome in the Latin Vulgate as anima and then as “soul” in the K.J.V., even though, as Alter points out, soul “strongly suggests a body-soul split—with implications of an afterlife—that is alien to the Hebrew Bible and to Psalms in particular.” The ancient Hebrew word for the shadowy underworld where the dead go, Sheol, was Christianized as “Hell,” even though there is no such concept in the Hebrew Bible. Alter prefers the words “victory” and “rescue” as translations of yeshu‘ah, and eschews the Christian version, which is the heavily loaded “salvation.” And so on. Stripping his English of these artificial cleansers, Alter takes us back to the essence of the meaning.

Monday, October 08, 2007

Canto 28: King of the Hill

With Canto 28, Dante is no longer being guided by Virgil; he's at liberty to explore the foresta at the top of the mountain. After the blasted landscapes of the preceding cantos, the canto opens upon a fragrant, cool, varicolored scene:

Vago già di cercar dentro e dintorno

la divina foresta spessa e viva,

ch'a li occhi temperava il novo giorno, 3

sanza più aspettar, lasciai la riva,

prendendo la campagna lento lento

su per lo suol che d'ogne parte auliva. 6

Un'aura dolce, sanza mutamento

avere in sé, mi feria per la fronte

non di più colpo che soave vento; 9

per cui le fronde, tremolando, pronte

tutte quante piegavano a la parte

u' la prim'ombra gitta il santo monte; 12

non però dal loro esser dritto sparte

tanto, che li augelletti per le cime

lasciasser d'operare ogne lor arte; 15

ma con piena letizia l'ore prime,

cantando, ricevieno intra le foglie,

che tenevan bordone a le sue rime, 18

tal qual di ramo in ramo si raccoglie

per la pineta in su 'l lito di Chiassi,

quand'Ëolo scilocco fuor discioglie.

Now keen to search within, to search around

that forest-dense, alive with green, divine-

which tempered the new day before my eyes, 3

without delay, I left behind the rise

and took the plain, advancing slowly, slowly

across the ground where every part was fragrant. 6

A gentle breeze, which did not seem to vary

within itself, was striking at my brow

but with no greater force than a kind wind's, 9

a wind that made the trembling boughs-they all

bent eagerly-incline in the direction

of morning shadows from the holy mountain; 12

but they were not deflected with such force

as to disturb the little birds upon

the branches in the practice of their arts; 15

for to the leaves, with song, birds welcomed those

first hours of the morning joyously,

and leaves supplied the burden to their rhymes- 18

just like the wind that sounds from branch to branch

along the shore of Classe, through the pines

when Aeolus has set Sirocco loose.

Both Italian and English from Opere.

As we arrive here, this third part of Purgatorio, it's probably a good idea to get some sense of orientation. What do we make of this place, and of how it's described, even before we learn more from its human(?) inhabitant? What do we understand to be the status of the pilgrim at this point? Having just completed his purgation, what seems to be the focus of this next step on his journey?

As we arrive here, this third part of Purgatorio, it's probably a good idea to get some sense of orientation. What do we make of this place, and of how it's described, even before we learn more from its human(?) inhabitant? What do we understand to be the status of the pilgrim at this point? Having just completed his purgation, what seems to be the focus of this next step on his journey? A little further on, allusions to several classical myths -- Aeolus; Dis and Proserpina; Venus, Cupid and Adonis; Hero and Leander -- along with Xerxes. What role in the seeming harmony of this moment does the introduction of these stories appear to play?

A little further on, allusions to several classical myths -- Aeolus; Dis and Proserpina; Venus, Cupid and Adonis; Hero and Leander -- along with Xerxes. What role in the seeming harmony of this moment does the introduction of these stories appear to play?And of course, what can we say of Matilda and her interaction with Dante and the other poets? Does Dante's first question to her seem odd?

Monday, October 01, 2007

Town vs. Gown: Classical (?) Christian Education in Idaho

The college handbook forbids students to embrace or promote “doctrinal errors” from the 4th through the 21st centuries, “such as Arianism, Socinianism, Pelagianism, Skepticism, Feminism.”Thanks to Shaw for pointing us to a fascinating story from the 9.30.07 New York Times about a private Idaho college that aims to incorporate classical learning into a curriculum that, the founder says, aspires to a "medieval" protestantism.

This reference, from deep in the story, might be worth looking at in light of Dante's project to situate classical and biblical traditions in and through his own work:

In the early 20th century, a Dutch theologian named Cornelius Van Til introduced a kind of theology called presuppositionalism. He argued that no assumptions are neutral and that the human mind can comprehend reality only if proceeding from the truth of biblical revelation. In other words, it is impossible for Christians to reason with non-Christians. presuppositionalism is a strangely postmodern theory that denies the possibility of objectivity — though it does not deny the existence of truth, which belongs to Christians alone.At one point the college's founder, Doug Wilson, says:

“There are circumstances in which I’d be in favor of execution for adultery. . . . I’m not proposing legislation. We’re saying, Let’s set up the Christian worldview, and our descendants 500 years from now can work out the knotty problems.”How prevalent might be Christians who'd agree to this matching their notion of "the Christian worldview?" Or, in the noble tradition of "What would Jesus do? (WWJD)" we can ask WWDS: "What would Dante say?"

Speaking of Dante's three dreams

As we look at the three dreams of the pilgrim (cantos 9, 19, 27), we might want to consider if, and how, they address the status of the pilgrim soul -- e.g., how might Dante have viewed Pelagianism, a heresy we glanced at when we were reading Augustine last year?

Pelagianism is a theological theory named after Pelagius. It is the belief that original sin did not taint human nature (which, being created from God, was divine), and that mortal will is still capable of choosing good or evil without Divine aid. Thus, Adam's sin was "to set a bad example" for his progeny, but his actions did not have the other consequences imputed to Original Sin. Pelagianism views the role of Jesus as "setting a good example" for the rest of humanity (thus counteracting Adam's bad example). In short, humanity has full control, and thus full responsibility, for its own salvation in addition to full responsibility for every sin (the latter insisted upon by both proponents and opponents of Pelagianism).

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)