At Mussy's suggestion, here's a piece on the Aeneid from the NY Times'

Connections - posted in full because the Times tends to limit access after a few days:

Out of Epic Wars, Another Epic Is Born, the One Called Civilization

By EDWARD ROTHSTEIN

Aeneas, as far as we can see, is spared the trauma of a hero’s death, the kind of prophesied calamity that brought Achilles down at the height of his powers. Instead, Aeneas is last seen, at the close of Virgil’s Aeneid, triumphantly planting his iron sword “hilt-deep in his enemy’s heart.” But has there been a time in recent memory when Aeneas’s literary corpse has not been wrestled over, when this Trojan warrior, brought to such vivid life by Virgil, has really been able to rest in peace?

Read now Robert Fagles’s new pulsing, lyrical translation of the Aeneid (Viking), with its eloquent mixture of high rhetoric and conversational ease, and see too if — as arguments rage over war and peace, civilization and barbarism — Aeneas stands a chance.

He suffers the fate of having an unsettled place in the pantheon of heroes because Virgil gives him a far grander role to play than Homer’s supra-human figures had in the Iliad and the Odyssey. Aeneas is not just a godlike tempestuous warrior like Achilles, who is gradually inducted into human culture with all its constraints and demands. He is not just a brilliant schemer like Odysseus, who simply wishes to return home after years of war and is buffeted by the tricks of gods and Fates and men.

Aeneas, the Trojan hero who carries his aged father on his shoulders out of his burning city, has a mission that reaches across history and stretches centuries into the future, a task that the gods remind him may not be avoided or shirked and that Virgil, writing in the third decade B.C., was beginning to see come to fruition. Aeneas’s task was to lead his fellow survivors of the great Trojan War onto the shores of Italy, where — after terrible battles — his descendants would eventually found Rome itself.

Aeneas was brought to epic life by Virgil at a time when a century of Roman civil war had come to an end, when Augustus’s leadership promised the establishment of the Roman Empire. And Aeneas is imagined creating a nation that, as Jove suggests, would “bring the entire world beneath the rule of law.”

That is what is at stake in the Aeneid. The individual hero must fulfill an imperial destiny. The goddess Juno, nursing an ancient grudge, strives to keep Aeneas from landing in Italy, then tries to keep him from surviving there, but his destiny is greater than any god’s mischief. It also forces Aeneas to jettison the love of Dido and lead the Trojans into yet another horrific war. This is a founding myth, resembling those of other ancient lands: there is a chosen people who must endure hardships and defeats for the promise of future glory. The trials test their leader, who himself will never see the new world established, though he makes it all possible.

But this is more than a national epic. It is not just about the founding of a country or the establishment of a people out of a ruinous past. Rome, the Aeneid implies (and we can imagine Virgil nodding to his patrons), will be more than a light unto the nations; it will establish a new form of governance. Aeneas is the founder of something we now call civilization.

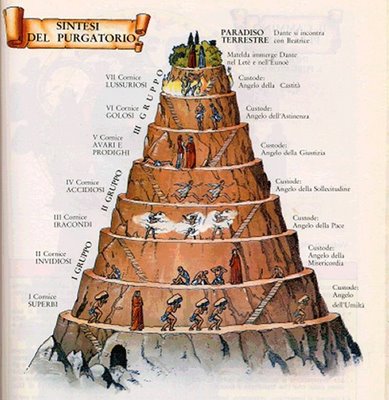

That, though, is where his posthumous trouble begins. Perhaps the Romans saw in Virgil’s meticulously described battles forerunners of Julius Caesar’s victories. (Caesar imagined, after all, that he was a descendant of Aeneas.) Perhaps in later eras Christianity could see hints of its own vision latent in the Aeneid. (Aeneas’s journey to the realm of the dead, after all, inspired Dante to make Virgil the experienced guide in his “Divine Comedy.”)

But in recent decades, when even the notion of civilization has come under challenge for its claims of ethical and social superiority, Aeneas has sometimes been portrayed as a kind of patsy for imperialism, mouthing higher goals while succumbing to reckless fury as he spills the bowels of his enemies on the earth. The argument has been made that Virgil’s project was actually ironic, anti-Augustan: he showed how civilization itself is drenched in blood, with self-celebratory history being written by the victors.

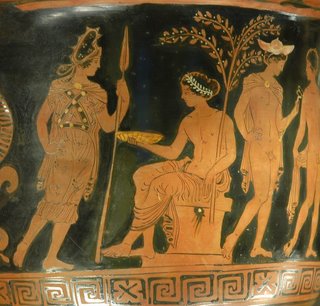

While Aeneas is supposedly held up as an embodiment of familial piety, he is so vulnerable to fury that he loses sight of things. As Troy burns, he glimpses the beauteous Helen, the root cause of the city’s destruction; “what joy, to glut my heart with the fires of vengeance,” he thinks, and he is about to take revenge on her when his mother, the goddess Venus, must remind him that his own family needs rescue.

Then, as he carries his father to safety, he forgets to look back and care for his wife, who is slaughtered. And at the very close of the epic he rejects a civilized appeal for restraint by his enemy Turnus and gives way to “savage grief” and “rage,” sending Turnus “down to the shades below.”

Glutting one’s heart with savage fires is not precisely something we imagine as a sign of civilization. And these battles for the future unfold with almost pornographic horror. Even Aeneas’s men, in the midst of recreational games, can whine for prizes, their vanity and passions stronger than any visions of communal good.

And yet, on his courageous descent into the Underworld, Aeneas is shown the unfolding of history, past and present. The shade of his revered father, Anchises, speaks of the future, specifying precisely what Rome’s achievement will be. Other civilizations he says, will “draw from the block of marble features quick with life” or “chart with their rods the stars that climb the sky.”

Others, that is, will be masters of the arts and sciences. Anchises says:

But you, Roman, remember, rule with all your power

the peoples of the earth — these will be your arts:

to put your stamp on the works and ways of peace,

to spare the defeated, break the proud in war.

The arts of rule: that is where Virgil himself says the triumph will be; the “rule of law” is how Jove puts it. As Virgil shows again and again, that rule is no small matter. It may be won by the sword; Aeneas, though, shows how much more is required. He displays compassion, delicacy, courage, insight into the vanquished, desire for an “eternal pact of peace.” These are all elements of civilization.

But can the sword ever be put aside, even with civilization’s triumph? Aeneas’s own frailties suggest that it cannot: he can “break the proud” but not always “spare the defeated.” The “works and ways of peace” are always vulnerable.

Jove himself, envisioning a Rome in which the Gates of War are welded shut, portrays the “frenzy of civil strife” as a live being, shackled, “monstrously roaring out from his bloody jaws.” Even when all intentions are good, there will be that persistent roar: misunderstandings, flaws, eruptions of desire, assertions of power — the mischief of the gods and the treachery of the heart.

This vision makes the Aeneid strong and somber and prescient, which is how Mr. Fagles’s English renders it. The Aeneid, he has suggested (thinking, he had said, of contemporary events), exhorts empires to behave. But it does not dismiss the ideal of civilization or the labors demanded or the persistent dangers faced; it offers a realist prophecy of war and peace, heralding civilization along with its discontents.