One would expect a work as potent as the Oresteia to build to an intense reversal -- a climax of peripatetic power yielding a satisfying denouement. But when the trilogy is taken as a whole, the powerfully energized scenes, some of the most memorable in all drama, involve the murder of the king in Agamemnon, and early scenes of the Furies in Eumenides.

Curiously, the moment late in Eumenides that turns Dike from automatonic vengeance to a mode of human Justice is not highly dramatized. I will explore this below and then address why I believe Aeschylus did it this way.

One way to summarize the story Aeschylus tells is this:

Ἀθηνᾶ

τάδ᾽ ἐγὼ προφρόνως τοῖσδε πολίταις

πράσσω, μεγάλας καὶ δυσαρέστους

δαίμονας αὐτοῦ κατανασσαμένη.

930πάντα γὰρ αὗται τὰ κατ᾽ ἀνθρώπους

ἔλαχον διέπειν.

ὁ δὲ μὴ κύρσας βαρεῶν τούτων

οὐκ οἶδεν ὅθεν πληγαὶ βιότου.

τὰ γὰρ ἐκ προτέρων ἀπλακήματά νιν

935πρὸς τάσδ᾽ ἀπάγει, σιγῶν δ᾽ ὄλεθρος

καὶ μέγα φωνοῦντ᾽

ἐχθραῖς ὀργαῖς ἀμαθύνει.

Note her emphasis on action (πράσσω). She is working to persuade the Furies to dwell in Athens, which calls for Athenians to accept that Dike itself is not separate from, but somehow is intertwined with, the powers of blood vengeance.

In agreeing on this, Athena, the Furies and the citizens remake the basis of Justice for the polis. Dike can no longer be realized through unmitigated brute vengeance, as in the isolate autocratic oikos. Yet while Dike of the polis seeks to use reason, it can not be formalized in a ratiocinative courtroom procedure hygienically unconscious of the horror of crime and the commensurate rage of Justice itself.

Vengeance and the rational verdict of truth enter into a negotiated "truce" that requires a Dike more complex than either of these modes on its own.

But how does one persuade ancient Erinyes to accept this strange new condition? For that matter, given that this new thing carries a potentially intractable opposition within it, how does one get mortal men to accept the presence of Furies within the polis?

Let's remember how Furies like their humans:

Χορός

ὀσμὴ βροτείων αἱμάτων με προσγελᾷ.

The moment of Persuasion is brief, a 34-line prose dialogue (lines 881-915) between two strong kommos segments. The exchange seems emotionally and rhetorically unremarkable compared with the vehement poetry preceding and the jubilant kommos that follows. Shorn of song, dance and poetic power, it presents the kind of negotiation found every day whether in the world of business, or politics, or familial relations -- two parties working out the terms of an agreement. No superpowers, no magical talismans, no oracles, presbyters or heraldic messengers need apply.

With all the Grand Guignol of Clytemnestra and the Erinyes that has come before, it might escape our notice that this exchange produces the peripeteia of the trilogy. What is special, when you consider it, is precisely the absence of any showy portrayal of the numinous. Power is spoken of in contractual terms, where we hear the Furies sound almost like teenagers talking to their mom:

Curiously, the moment late in Eumenides that turns Dike from automatonic vengeance to a mode of human Justice is not highly dramatized. I will explore this below and then address why I believe Aeschylus did it this way.

One way to summarize the story Aeschylus tells is this:

- Long ago, Athens needed to put in place a new, civil kind of Dike to replace primal, unreflective vengeance.

- To that end, Apollo and Athena devise a form providing for a jury of citizen peers to decide guilt or innocence after hearing testimony from accuser and defendant.

- This proves unacceptable to the Furies -- powers older than the Gods who react immediately to familial violence without deliberative procedures.

- Apollo would banish the Furies -- set them outside of Athenian Justice. Athena doesn't agree, and achieves a different resolution.

Ἀθηνᾶ

τάδ᾽ ἐγὼ προφρόνως τοῖσδε πολίταις

πράσσω, μεγάλας καὶ δυσαρέστους

δαίμονας αὐτοῦ κατανασσαμένη.

930πάντα γὰρ αὗται τὰ κατ᾽ ἀνθρώπους

ἔλαχον διέπειν.

ὁ δὲ μὴ κύρσας βαρεῶν τούτων

οὐκ οἶδεν ὅθεν πληγαὶ βιότου.

τὰ γὰρ ἐκ προτέρων ἀπλακήματά νιν

935πρὸς τάσδ᾽ ἀπάγει, σιγῶν δ᾽ ὄλεθρος

καὶ μέγα φωνοῦντ᾽

ἐχθραῖς ὀργαῖς ἀμαθύνει.

Athena

I act zealously for these citizens in this way, settling here among them divinities great and hard to please. For they have been appointed to arrange everything among mortals. Yet the one who meets their oppression does not know where the blows of life come from. For the sins of his fathers drag him before them; destruction, in silence and hateful wrath, levels him to the dust, for all his loud boasting.

[Eum. 928-35] (Smyth adapted using Sommerstein's reading)

Note her emphasis on action (πράσσω). She is working to persuade the Furies to dwell in Athens, which calls for Athenians to accept that Dike itself is not separate from, but somehow is intertwined with, the powers of blood vengeance.

In agreeing on this, Athena, the Furies and the citizens remake the basis of Justice for the polis. Dike can no longer be realized through unmitigated brute vengeance, as in the isolate autocratic oikos. Yet while Dike of the polis seeks to use reason, it can not be formalized in a ratiocinative courtroom procedure hygienically unconscious of the horror of crime and the commensurate rage of Justice itself.

Vengeance and the rational verdict of truth enter into a negotiated "truce" that requires a Dike more complex than either of these modes on its own.

But how does one persuade ancient Erinyes to accept this strange new condition? For that matter, given that this new thing carries a potentially intractable opposition within it, how does one get mortal men to accept the presence of Furies within the polis?

Let's remember how Furies like their humans:

Χορός

ὀσμὴ βροτείων αἱμάτων με προσγελᾷ.

The smell of human blood is smiling at me. (Eum. 253)

|

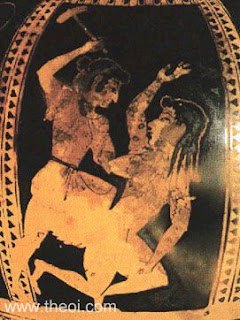

| Dike and Adikia |

The moment of Persuasion is brief, a 34-line prose dialogue (lines 881-915) between two strong kommos segments. The exchange seems emotionally and rhetorically unremarkable compared with the vehement poetry preceding and the jubilant kommos that follows. Shorn of song, dance and poetic power, it presents the kind of negotiation found every day whether in the world of business, or politics, or familial relations -- two parties working out the terms of an agreement. No superpowers, no magical talismans, no oracles, presbyters or heraldic messengers need apply.

With all the Grand Guignol of Clytemnestra and the Erinyes that has come before, it might escape our notice that this exchange produces the peripeteia of the trilogy. What is special, when you consider it, is precisely the absence of any showy portrayal of the numinous. Power is spoken of in contractual terms, where we hear the Furies sound almost like teenagers talking to their mom:

Chorus

Lady Athena, what place do you say I will have?

Athena

One free from all pain and distress; please accept it.

Chorus

Say that I have accepted it, what honor awaits me?

Athena

That no house will flourish without you.

Chorus

Will you gain for me the possession of such power?

Athena

Yes, for we will raise up the fortunes of those who honor you.

Chorus

And will you give me a pledge for all time?

Athena

It can be done; I need not say what I will not accomplish.

Chorus

It seems your spells (θέλξειν) enchant; we're letting go our anger.

Athena

Then stay in the land and you will gain other friends.

Chorus

What blessings then do you advise me to invoke on this land? (Eum. 892-902)

The "spells" or "enchantments" (θέλξειν) the Furies speak of here do not resemble typical magic spells. Such enchantments here have more to do with the character of an exchange in which these primeval beings are addressed in a modern respectful tone and promised a dignified role within an altered polis.

Letting go our anger is adapted from Smyth. Sommerstein has I am moving away from my anger.

The words are μεθίσταμαι κότου; κότου can mean ill will, rancor, fury. The verb μεθίσταμαι derives from meta + ίσταμαι: a setting over; substituting one thing for another; changing or putting this for that.

The words are μεθίσταμαι κότου; κότου can mean ill will, rancor, fury. The verb μεθίσταμαι derives from meta + ίσταμαι: a setting over; substituting one thing for another; changing or putting this for that.

With this mitigation the Furies are no longer quite so enraged, and their power of the curse can be turned. They now ask:

τί οὖν μ᾽ ἄνωγας τῇδ᾽ ἐφυμνῆσαι χθονί; 902

This question receives different treatments:

All of which might underscore the unprecocious, plain style of this prose scene. A major change is occurring here, but is not dramatized -- it takes place in a manner that is virtually tacit, unmarked.

What of it? For one thing, the modality of Athena's persuasion here relies as little upon seductive rhetorical power as it does upon logical argument. What persuades the Furies is the promise of a complex substitution -- of a home for no home, a new use for old rancor, a new status within the polis.

Athena describes this new interrelation of unchanged elements earlier in the courtroom scene, right before the jurors vote.

Ἀθηνᾶ

τὸ μήτ᾽ ἄναρχον μήτε δεσποτούμενον

ἀστοῖς περιστέλλουσι βουλεύω σέβειν,

καὶ μὴ τὸ δεινὸν πᾶν πόλεως ἔξω βαλεῖν.

τίς γὰρ δεδοικὼς μηδὲν ἔνδικος βροτῶν;

Smyth translates δεινὸν as "fear," but the word bears a richer sense of wondrous awe-inspiring terror and strangeness. Sophocles uses it to speak of man in Antigone. Athena is counseling the citizens to defend and respect δεινὸν. She yokes Dike to δεινὸν and to anger, ending these words of counsel with:

κερδῶν ἄθικτον τοῦτο βουλευτήριον,

705αἰδοῖον, ὀξύθυμον, εὑδόντων ὕπερ

ἐγρηγορὸς φρούρημα γῆς καθίσταμαι.

I'll take a stab at one way of looking at it.

This coming into being is a kind of creation, but not a birth -- instead of a natural product of organic generation, something new is brought about through a substitution (μεθίσταμαι). The Furies' form of vengeance was bound up with blood ties -- familial bonds. What happens here brings the shock of a non-generative act of conception.

Athena is like a midwife enabling the citizens and Furies to put something new into the world, instantly -- not unlike the birth of Athena from the cranium of Zeus. Except that instead of the new reality of an unmothered goddess, there's a contractual fiat. Citizens and furies remain who they are, but agree to henceforth mean something new by Dike. Athena is bringing them to make a new meaning for an old word.

What's dramatized here is the power, not of gods, but of human language to slip something new into the world -- something that hitherto was nameless -- by taking and using an old word. What was called "Justice" now names something quite different from what it used to mean, both for the Furies and the citizens.

This yoking of old and new seems not unlike an act of language act known to and analyzed by the ancient grammarians. The imposition of a new meaning upon an existing word describes what they knew as catachresis. When a word is torn from its proper meaning in the system of signs to assume a new signification, catachresis occurs.

The root sense of catachresis is "abuse" or "error," as when a word is perceived to be used improperly because everybody knows its proper meaning is something else. The traditional example that always comes up offers something of the violence of this abuse: When a word for the structural support of a table was needed, the word "leg" was torn from its organic connection to our body and given a new, completely inorganic meaning.

Due to the slipperiness of language, its openness to err, be abused or misused, the legs we stand on can run off to mean the structures that a table or chair "stands" on. While Apollo would vociferously disapprove of such license taken with the proper names for things, others defend certain acts of catachresis as necessary, enabling the unutterable to achieve speech.

Improper meanings soon lose their newness and become the new proper. We don't usually flinch when touching the arm of a chair. Athena promises the Furies will "have a share in the land" -- γαμόρῳ χθονὸς (890) -- i.e., dwelling on property they properly hold.

Persuaded by Athena, the Furies and the citizens accept a new complex sense for Dike. If "polis" had been defined as what is NOT the Furies, now those creatures live under it, as a newly installed proper meaning lives "under" an old word.

So the peripeteia of the Oresteia can be said to turn on catachresis -- speaking a Dike that hitherto would have been mute. This doesn't happen through the agency of some numinous mythological power represented in the scene. It arrives via a contractual agreement between humans and gods through the power of speech, in prose.

No discussion of this brief scene is complete without the magnificent speech Athena offers in answer to the question of the Erinyes:

That's Smyth without alteration. There is no noun that means "blessings" in the passage. Athena simply assumes whatever the Furies meant by ἐφυμνῆσαι is understood. So the passage could read

Song or chant sets tone and inspire, but there is no magic spell. The onus of Dike is on the people.

What's true is that what we all see here, what Athena shares with all in common, is the face of Nature undistorted by dreams or passions. After all the vivid images of houses haunted by the cries of eaten children, of murdered tyrants, of the Furies' pursuit of human blood, this countenance of the world present to the eye in simple, everyday words comes with the shock of an awakening. We are not seeing through the eyes of Furies or murderers or captives or haunted children, but through the eyes of Athens. Yes, Athena is the speaker -- but if an Athenian described the earth and sea and sky like this, we wouldn't bat an eye.

Except for one part.

The result is an absurd image of one who does not simply put things into the earth, but cares for them, gathers them in flocks and leads them (along the path of good speech) to green pastures. The fusion of gardening and herding marries the idealism of culture with the praxis of political action.* It could be considered a new word, or a "blend," but as a synthesis of two old words making something new, we might also think of it as a double catachresis of its own playful invention.

I'll wrap this up soon -- promise.

τί οὖν μ᾽ ἄνωγας τῇδ᾽ ἐφυμνῆσαι χθονί; 902

This question receives different treatments:

Smyth: What blessings then do you advise me to invoke on this land?The verb -- ἐφυμνῆσαι -- seems unusual. Liddell and Scott and other dictionaries I've consulted agree that it means sing, or chant. This would allow:

Sommerstein: So what blessings do you bid me invoke upon this land?

Lattimore: I will put a spell upon the land. What shall it be?

What then would you have us chant for the land?The emphasis is placed on voice, the act of chanting or singing.

All of which might underscore the unprecocious, plain style of this prose scene. A major change is occurring here, but is not dramatized -- it takes place in a manner that is virtually tacit, unmarked.

What of it? For one thing, the modality of Athena's persuasion here relies as little upon seductive rhetorical power as it does upon logical argument. What persuades the Furies is the promise of a complex substitution -- of a home for no home, a new use for old rancor, a new status within the polis.

Athena describes this new interrelation of unchanged elements earlier in the courtroom scene, right before the jurors vote.

Ἀθηνᾶ

τὸ μήτ᾽ ἄναρχον μήτε δεσποτούμενον

ἀστοῖς περιστέλλουσι βουλεύω σέβειν,

καὶ μὴ τὸ δεινὸν πᾶν πόλεως ἔξω βαλεῖν.

τίς γὰρ δεδοικὼς μηδὲν ἔνδικος βροτῶν;

Athena

Neither anarchy nor tyranny—this I counsel my citizens to defend and respect, and not to drive strange terror (δεινὸν) wholly out of the city. For who among mortals, if he fears nothing, is righteous? (Eum. 696-99)Interiorizing the Furies within the polis is not possible without the assent of both the citizens and the Furies to a fundamental change in their relations with one another. They each are themselves unchanged; the way they interrelate is new.

Smyth translates δεινὸν as "fear," but the word bears a richer sense of wondrous awe-inspiring terror and strangeness. Sophocles uses it to speak of man in Antigone. Athena is counseling the citizens to defend and respect δεινὸν. She yokes Dike to δεινὸν and to anger, ending these words of counsel with:

κερδῶν ἄθικτον τοῦτο βουλευτήριον,

705αἰδοῖον, ὀξύθυμον, εὑδόντων ὕπερ

ἐγρηγορὸς φρούρημα γῆς καθίσταμαι.

I establish this tribunal, untouched by greed, worthy of reverence, quick to anger, awake on behalf of those who sleep, a guardian of the land. (Eum. 704-06)But what kind of new relation is this? How can we come to terms with this curious yoking of old and new?

I'll take a stab at one way of looking at it.

This coming into being is a kind of creation, but not a birth -- instead of a natural product of organic generation, something new is brought about through a substitution (μεθίσταμαι). The Furies' form of vengeance was bound up with blood ties -- familial bonds. What happens here brings the shock of a non-generative act of conception.

Athena is like a midwife enabling the citizens and Furies to put something new into the world, instantly -- not unlike the birth of Athena from the cranium of Zeus. Except that instead of the new reality of an unmothered goddess, there's a contractual fiat. Citizens and furies remain who they are, but agree to henceforth mean something new by Dike. Athena is bringing them to make a new meaning for an old word.

What's dramatized here is the power, not of gods, but of human language to slip something new into the world -- something that hitherto was nameless -- by taking and using an old word. What was called "Justice" now names something quite different from what it used to mean, both for the Furies and the citizens.

This yoking of old and new seems not unlike an act of language act known to and analyzed by the ancient grammarians. The imposition of a new meaning upon an existing word describes what they knew as catachresis. When a word is torn from its proper meaning in the system of signs to assume a new signification, catachresis occurs.

The root sense of catachresis is "abuse" or "error," as when a word is perceived to be used improperly because everybody knows its proper meaning is something else. The traditional example that always comes up offers something of the violence of this abuse: When a word for the structural support of a table was needed, the word "leg" was torn from its organic connection to our body and given a new, completely inorganic meaning.

Due to the slipperiness of language, its openness to err, be abused or misused, the legs we stand on can run off to mean the structures that a table or chair "stands" on. While Apollo would vociferously disapprove of such license taken with the proper names for things, others defend certain acts of catachresis as necessary, enabling the unutterable to achieve speech.

Improper meanings soon lose their newness and become the new proper. We don't usually flinch when touching the arm of a chair. Athena promises the Furies will "have a share in the land" -- γαμόρῳ χθονὸς (890) -- i.e., dwelling on property they properly hold.

Persuaded by Athena, the Furies and the citizens accept a new complex sense for Dike. If "polis" had been defined as what is NOT the Furies, now those creatures live under it, as a newly installed proper meaning lives "under" an old word.

So the peripeteia of the Oresteia can be said to turn on catachresis -- speaking a Dike that hitherto would have been mute. This doesn't happen through the agency of some numinous mythological power represented in the scene. It arrives via a contractual agreement between humans and gods through the power of speech, in prose.

|

| Varvakeion Athena |

No discussion of this brief scene is complete without the magnificent speech Athena offers in answer to the question of the Erinyes:

Chorus

What blessings then do you advise me to invoke on this land?

Ἀθηνᾶ

ὁποῖα νίκης μὴ κακῆς ἐπίσκοπα,

καὶ ταῦτα γῆθεν ἔκ τε ποντίας δρόσου

905ἐξ οὐρανοῦ τε: κἀνέμων ἀήματα

εὐηλίως πνέοντ᾽ ἐπιστείχειν χθόνα:

καρπόν τε γαίας καὶ βοτῶν ἐπίρρυτον

ἀστοῖσιν εὐθενοῦντα μὴ κάμνειν χρόνῳ,

καὶ τῶν βροτείων σπερμάτων σωτηρίαν.

910τῶν εὐσεβούντων δ᾽ ἐκφορωτέρα πέλοις.

στέργω γάρ, ἀνδρὸς φιτυποίμενος δίκην,

τὸ τῶν δικαίων τῶνδ᾽ ἀπένθητον γένος.

ὁποῖα νίκης μὴ κακῆς ἐπίσκοπα,

καὶ ταῦτα γῆθεν ἔκ τε ποντίας δρόσου

905ἐξ οὐρανοῦ τε: κἀνέμων ἀήματα

εὐηλίως πνέοντ᾽ ἐπιστείχειν χθόνα:

καρπόν τε γαίας καὶ βοτῶν ἐπίρρυτον

ἀστοῖσιν εὐθενοῦντα μὴ κάμνειν χρόνῳ,

καὶ τῶν βροτείων σπερμάτων σωτηρίαν.

910τῶν εὐσεβούντων δ᾽ ἐκφορωτέρα πέλοις.

στέργω γάρ, ἀνδρὸς φιτυποίμενος δίκην,

τὸ τῶν δικαίων τῶνδ᾽ ἀπένθητον γένος.

τοιαῦτα σοὔστι. τῶν ἀρειφάτων δ᾽ ἐγὼ

πρεπτῶν ἀγώνων οὐκ ἀνέξομαι τὸ μὴ οὐ

915τήνδ᾽ ἀστύνικον ἐν βροτοῖς τιμᾶν πόλιν.

πρεπτῶν ἀγώνων οὐκ ἀνέξομαι τὸ μὴ οὐ

915τήνδ᾽ ἀστύνικον ἐν βροτοῖς τιμᾶν πόλιν.

Athena

Blessings that aim at a victory not evil; blessings from the earth and from the waters of the sea and from the heavens: that the breathing gales of wind may approach the land in radiant sunshine, and that the fruit of the earth and offspring of grazing beasts, flourishing in overflow, may not fail my citizens in the course of time, and that the seed of mortals will be kept safe. May you make more prosperous the offspring of godly men; for I, like a gardener (φιτυποίμενος), cherish the race of these just men, free of sorrow. (Eum. 903-12)

That's Smyth without alteration. There is no noun that means "blessings" in the passage. Athena simply assumes whatever the Furies meant by ἐφυμνῆσαι is understood. So the passage could read

Songs (or chants) that aim at a victory not evil; songs from the earth and from the waters of the sea and from the heavens:

Song or chant sets tone and inspire, but there is no magic spell. The onus of Dike is on the people.

What's true is that what we all see here, what Athena shares with all in common, is the face of Nature undistorted by dreams or passions. After all the vivid images of houses haunted by the cries of eaten children, of murdered tyrants, of the Furies' pursuit of human blood, this countenance of the world present to the eye in simple, everyday words comes with the shock of an awakening. We are not seeing through the eyes of Furies or murderers or captives or haunted children, but through the eyes of Athens. Yes, Athena is the speaker -- but if an Athenian described the earth and sea and sky like this, we wouldn't bat an eye.

Except for one part.

I, like a gardener (φιτυποίμενος), cherish the race of these just men, free of sorrow. (911)One would be remiss not to note this wonderful word φιτυποίμενος, which may have been underserved by Smyth.

Lattimore: as the gardener works in love. so love I best of all the unblighted generation of these upright men.

Sommerstein: like a shepherd of plants, I cherish the race to which these righteous men belong.Where Smyth and Lattimore settle for "gardener," Sommerstein discovers the remarkable strangeness of φιτυποίμενος, which yokes two distinct modes of agrarian work: herding and planting. His fine "shepherd of plants" fuses the dynamics of herding with the sowing of seeds.

The result is an absurd image of one who does not simply put things into the earth, but cares for them, gathers them in flocks and leads them (along the path of good speech) to green pastures. The fusion of gardening and herding marries the idealism of culture with the praxis of political action.* It could be considered a new word, or a "blend," but as a synthesis of two old words making something new, we might also think of it as a double catachresis of its own playful invention.

I'll wrap this up soon -- promise.

*I belatedly find that Gilles Deleuze had pondered this very catachresis (apparently without reference to Aeschyus) in his Seminar on Foucault 1985-86, part II.